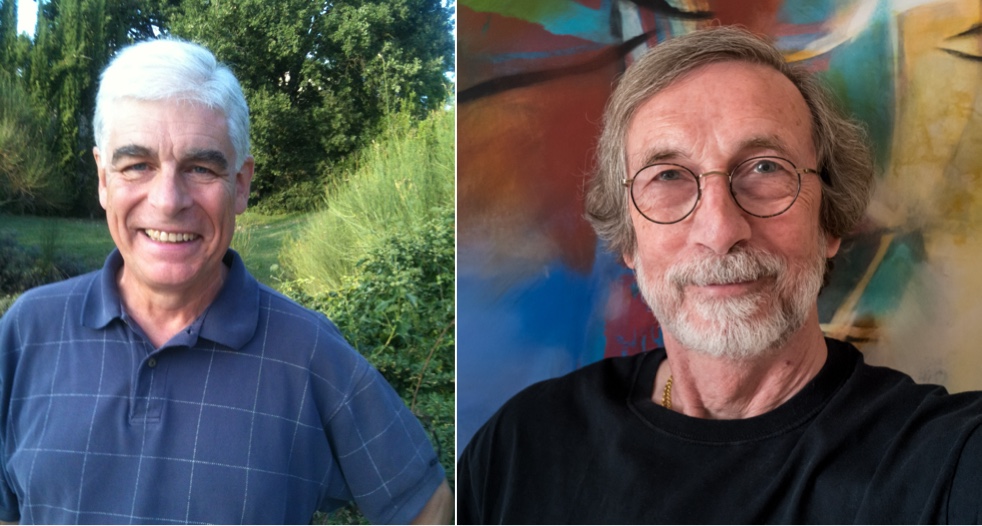

Martin Thomas and Mick Yates, two friends I admire, come to the Swamp to share their encore stories and second acts. Both men returned to university late in their professional careers and that decision changed the trajectory of their lives, the focus of their commitments and how they have chosen to make a difference as they conjure up second acts and most likely, third and forth acts. All of us will learn a few things about how to design a life well lived.

Links

Martin Thomas

Mick Yates

EPISODE 54

[INTRODUCTION]

[0:00:06] ANNOUNCER: You are listening to 10,000 Swamp Leaders, leadership conversations that explore adapting and thriving in a complex world with Rick Torseth and guests.

[0:00:20] RT: Hi, everybody. This is Rick Torseth. And this is 10,000 Swamp Leaders. We are the podcast. We are the place where we have conversations with people who have made decisions in their life, either personal or professional, to lead. And we want to learn a little bit about what that involves. What does it entail? Lessons learned. Successes. Failures. Breakdowns. Humorous stories. Whatever it is when can conjure up. And I say all that because that’s a little different than my normal intro. Because I have two friends of mine that I’ve known for about 15 to 17 years, I’m going to guess, Martin Thomas and Mick Yates. Both Englishmen who I met in a program that we’ll talk a little bit about, I’m sure, as part of our conversation here in an education program that we did at Oxford and HEC in Paris.

I’ve asked Mick and Martin to join me because they’ve lived some pretty interesting times and lives and have some great leadership experiences both professionally and personally. And so, we’re going to dig into that a little bit.

First of all, gentlemen, I want to welcome both of you, Martin and Mick, to the swamp. Welcome

[0:01:21] MT: Thank you.

[0:01:22] MY: Thank you for having us.

[0:01:23] RT: All right. We’ll do this dance. I’ll manage this conversation so you don’t tremble all over each other. I’m going to ask you both to share with the listeners a little bit about what you think you want them to know about you so they have some orientation. Mick, why don’t you go first?

[0:01:39] MY: I knew you were going to ask me. What would I like people to know? I never thought of myself as a leader, first of all. How about that?

[0:01:46] RT: That’s a good start.

[0:01:47] MY: My career, I was at Procter & Gamble for over 20 years. Most of it internationally. I strolled over in Japan actually. Then I was doing something similar for J&J where I was the chairman for the Asia Pacific consumer business. My background is global, which is actually a big part of my story, I think.

And I was lucky enough to parley that into some social development work. My wife and I founded a program in Cambodia. Building schools in the Khmer Rouge areas. I used to be a bit of a swat, to use an English word at school. I was very serious about my studies at school until I got to University. And then somehow sex, drugs and rock and rolls got in the way. I don’t know quite what it was. But it was the 60s after all. And I got into student politics. In a way, I was an accidental businessman.

When I quit the big corporate, I ended up in the data business, big data business, which was relatively new in those days. Now everybody does it. And all through my life, I’ve been a photographer. And my current venture is I’m co-founder of a photo festival, which ironically – well, not ironically. I suppose it’s good. It uses all my skills basically. Everything I kind of learned in all these different things.

And along the way, as you said, Rick, we did this program at Oxford and HEC. Decided to go back to the school being such a lousy student in my undergrad years. And I did a master’s on change management. And I also recently did a master’s on photography. I’ve been collecting degrees. Now I’m actually a professor in the ethics department at the University of Leeds. I kind of keep busy.

[0:03:21] RT: That’s an extreme overreaction for sex, drugs and rock and roll in university when you’re younger. But we’ll come back to that one.

[0:03:26] MY: I’ve been trying to compensate my entire life.

[0:03:30] RT: All right. Mr. Thomas Martin, why don’t you introduce yourself to everybody?

[0:03:35] MT: Hi. Well, not at all like Mick. I joined Unilever. Whereas he was at Procter & Gamble. But I joined as a school leaver. Qualified as an accountant. And really was looking for an international career. Very much like Mick. And I qualified. I took a year out to do a master’s in financial control at Lancaster University, which was one of the new universities at the time that was offering postgraduate programs to people that were qualified in a professional way, as I was, and with work experience, which I had.

And although I was not much of a swat at school, much more interested in sports than studying. I did really take to the opportunity as a sort of 22-year-old of being able to really get involved in studying subjects that I wouldn’t have thought that I’d be interested in, to be honest.

I got myself a master’s in financial control with specializations really within that of investment analysis and of accounting theory. Neither of which I would have thought initially would have captured my imagination. But, really, they showed up to my mind the inadequacy of the accounting profession.

And in particular, the limited scope of viability of financial accounting as it was practiced then and more or less it’s the same today. Except that the world has moved on and the world has moved on to go way beyond simple financial performance in what organizations are trying to show to the world. And basically, that’s ended up back in the laps of the accountants who really don’t have a clue as to how to go about it.

I’ve used the change management program that Mick and I both followed, and you, Rick, as a springboard into looking at some of those other dimensions. In particular, the human dimension, and trying to put together ways in which we really could start to look at performance on a broader front, including social and environmental performance. But, of course, alongside economic performance. Which, when you think in sustainability terms, is an absolute must to have. Because everything else rides on financial viability.

[0:06:35] RT: Okay.

[0:06:36] MT: Yeah. Sorry. Maybe it’s too much of an explanation. But that’s how I got into it. And that’s what I’ve been following ever since with not much success, I’ve got to say.

[0:06:47] RT: All right. Perfect intro then. Okay. When I was pitching this idea up to the two of you, Martin, you came across in an exchange with the three of us that saying you’d like to do it, but you really didn’t think you had much to offer. And I’m thinking to myself au contraire. And I say that in the context of how you’ve chosen to use yourself in your work.

And I met you both – and we’re going to get into this a little further down the road. But I met you both through this program that you’re referencing, came on a few years after you had been there. You’re in the first group. I want to get into it a little bit. And we’ll come back to your work here. But at that point, you were fairly long in your career and you had track records of success and achievement. The question is why at that point in life go back to school and put yourself through the rigor, and the cost and the time to educate yourself? And we should say, broadly speaking, this program was about change. And I’ll leave it to you to be more nuanced than that in terms of your own perspective. But what drew you back into an education environment for the sake of you? Mick, why don’t you go first?

[0:07:58] MY: Yeah. The program you’re referencing was called – or still is actually, called Consulting and Coaching for Change. And it’s at Oxford and HEC. I’d left corporate, big corporate, a couple years before I got on this first program, which had where Martin and I met. It would be in 2003.

At that time, I was 53 years old, I guess, to be exact. I did it because, well, partly the jokey reason. I wanted to kind of make up for my undergrad years. But also, I figured I’ve always thought of learning as something you should be doing all the time. There was something to pick up. And I looked around and thought, “Oh, this could be quite cool.” And I was looking at getting into the consulting business, which I did a little, but it wasn’t really the main thing. But it just seemed like a good way to get back and I guess put a little rigor around the things that I thought I knew.

I can’t speak for Martin, except – kind of can. But we both came in knowing everything, right? I think because we’ve been doing it for so long. But I think the idea of the program was to kind of give us a different way to think about stuff that we kind of knew and put some frameworks on it. That’s about it. Yeah.

[0:09:08] RT: Okay. And Martin, what drew you to going back to school?

[0:09:12] MT: Well, many parallels with what Mick has just said. I’d left corporate. I was doing a bit of consulting. I was doing some interim management. I’d set up my own company, which is Call for Change. And when I looked at what I could be offering, I’ve been managing change management programs in corporates and in my post-Unilever.

And a lot of what they were looking for was managing the implementation of mega systems implementations. And they were all going wrong. Because when I looked at it, it was the mismanagement of people and the human dimension, which for me was causing the problems in almost all the implementations. And there were others.

I mean, mergers and acquisitions were going down the same road because people thought it was just top-down. You just plan. Roll it out. Implement it. Hammer it in. And people get on with it.

[0:10:24] RT: You so you signed up for this deal to do what then in the context of that?

[0:10:30] MT: Because I was qualified as a finance analyst, as an accountant, a commercial financial manager. But I had no qualification in change management per se. And so, for me, the advertisement in The Economist that said there’s this bicultural, as you say, Oxford program dealing for a year with change management and the human dimension thereof. I thought, “This is worth it.” I was actually finishing one assignment when I read that advertisement. And I applied for it immediately. Because at the time, I had the resources. I had the – certainly, the ambition was there. And when I met up with the people on it, then it really kicked off. Because they were exceptional people.

[0:11:25] RT: And we should say that, not for me, but for you two and the people that you started this program with, this was a bit of a flyer. Because this was the very first version of this program. There was no track record. There was no references. There were no people you could talk to who had done the program before you decided to give them your money and time.

There’s a leap there of some sense of faith that this would turn out for you. I’m interested in the learning process of what you experienced here. Off you go. What surprised you about yourself? Mick, you made the comment. You show up there thinking you know all the answers. I know that’s partially tongue-in-cheek. And, also there’s some credibility to that. What surprised you about yourself as a student at an advanced stage that caught you out? And what surprised you about your experiences in life that prepared you for this education experience? There are two questions there.

[0:12:26] MY: Yeah. There’s a lot in that. And advanced stage at 53. That’s quite a statement.

[0:12:31] RT: Yeah.

[0:12:32] MY: But what surprised me the most, I think actually it’s what Martin just said, was the other people. I think, truthfully, we got at least as much out of that first module from each other as we got from the program itself. And it’s fair to say that we collectively offered suggestions on how to improve the program. And that’s not tongue-in-cheek. That actually did happen.

We were talking about that with the founding academics that were running the program at that point, Elizabeth and Denny just a few weeks ago. Anyway, it was the other people, I think, and their experiences.

And I think then it started to dawn on me that I could put a framework on what I’d been doing all my life. And not just a framework and the skills that I’d been using or that I learned in these various businesses. But also, how then to communicate it to other people. I had always seen my job in the business is teaching people. That’s always been a big thing for me. As much as anything else, it was a way for me to think about how to teach other people using a few frameworks that were useful.

[0:13:36] RT: Okay.

[0:13:37] MY: That’s probably the sum up.

[0:13:38] RT: Martin, what surprised you?

[0:13:41] MT: What surprised me most was my ability to see things through completely new lenses, which I had not even imagined at the time. I thought this was going to be more you know better programmatic change, basically. And I was prepared to learn that because I’d not done anything about it in what I’ve done previously. Not from an academic point of view. Not from a different way of thinking.

And when I got into thinking of my own limits and the very blinkered way of my worldview, I thought, “This is the opportunity to think differently and engage people.” And I surprised myself by being so interested in that. And, by the way, it opened my mind to the stuff that I’d learned on my first master’s program in the early 70s that I’d never really resolved. Because that which you can apply in business, you learn, and you practice, and you get used to it and you embed it in the way you think and work.

The stuff that I’d put on one side, because it was too tough to deal with in business, such as putting people on the balance sheet. It was when I came to think about what we were doing on the consulting and coaching for change program and afterwards that I realized that a lot of that was valid. And it have been stored away, unused, because it was unwelcome in the organizations that I was working with.

[0:15:35] RT: Yeah. Okay. For people who are listening, a tiny bit of structure to this program. It consists of about six modules. Roughly six weeks apart. They would alternate between Oxford and Paris. And there was this cohort of people, anywhere from 20 to 30 people, who were on this journey every year. But you all were on the first journey.

I’m interested. Mick, you touch on this briefly. But I’d like maybe to expand it. There are two kinds of learning going on here. There are the people standing in the front of the room who came prepared to deliver modules on change and varying other aspects that they thought would be relevant to the program even if you were pushing back a little bit on some of that. But then there’s the other program which we’re all familiar with in this kind of education journey, where there’s the after-hours. There are the dinners. There are the meals. There are the other kinds of conversations that you’re having with the people you’re on this journey with.

For your perspective, to what extent has that part of the learning journey that you were on shaped the value you got out of the program and also who you are as a person independent of particular professional work? This is more of a personal side. Martin, I’m going to start with you and make Mick wait a little bit.

[0:16:49] MT: We both have mentioned already that the people on the program were exceptional. None of us had corporate sponsorship. Because, as you say, there was no track record. But we both knew and a lot of other people knew that an Oxford, and I should say leadership, those brands of academic thought and work were pretty strong guarantees that this was going to have some substance.

And the minute that we met, and our evenings at the bar and what happened before breakfast and our meetings to get to – once we realized that we’ve got something that we wanted to build upon, which ended up being called the change leaders, we worked at that and we knew that we’d have to do not only what we needed to get our degrees. And we all got distinctions. Not all the programs. But the founders of the change leaders got good grades. And we knew that, above and beyond that, we wanted to create something which would involve us together. Working together if we could. Certainly, learning together. And, of course, socializing together.

And so, that spark ran through the rest of the program. Because we knew that when we left our very first module together that we weren’t going to leave it. We weren’t going to ditch this experience. This was an opportunity that we really needed to build upon. And we did.

[0:18:41] RT: Okay. Well, we’ll come back to that. I want to pick that up. But, Mick, why don’t you go jump in here with your thoughts?

[0:18:47] MY: Well, No. Just it’s terrible because we keep agreeing with each other, which is not normally the case. But I agree with Martin on this. That was exactly what happened. We decided we wanted to keep going. And we literally decided that very first module to try to create some kind of community practice going forward. Those were the keywords actually, community practice.

It was about seeing if we could help each other’s business. Seeing if we can help each other’s development. And then, basically, providing a forum for conversation about some of the issues that were important to us. Yeah, a lot of it happened in the bar. We shouldn’t be advertising too much for Oxford and actually say. But in those days, Oxford had a particularly good wine cellar. Yeah, we came out of that first module at least as committed to create a new community practice as we were frankly to finish the degree.

[0:19:38] RT: Yeah.

[0:19:38] MY: There were some of our members that didn’t finish the degree. And there were some of the members that did the course but didn’t do the diploma. And there were some that did the course but didn’t do either the diploma or the degree. But they just finished the course.

I would say that we were – well, personally anyway, at least as committed to getting something going for the future as we were to finishing the program. Coming out of the gates really.

[0:20:03] RT: Okay. We’re definitely going to come back to this. But I want to stay for the moment the immediate period. How did the work you did in the program affect your life professionally coming out of it?

[0:20:16] MY: Are you talking to me or Martin on this?

[0:20:18] RT: Mick, you go ahead.

[0:20:20] MY: I should have said this at the beginning. I was actually quite interested in the academic process. I was actually quite intrigued by how that worked. How you did research. How you did the references? How you put it all together. And I didn’t really have a career goal out of it. It was just I was interested in the process. I wasn’t going to do anything with it.

As it turns out, I do something with it because I’m a visiting professor at university. But at that point, it was like, “No. I’m just interested in this process.” And it was pretty rigorous. You had to do the papers every module. Put something in that was useful. You got feedback on it. And eventually did the final dissertation for the degree.

But that I think ditched at me in quite a good steed. I sort of kept those habits. I’ve got a – you can’t see it because it’s a podcast. But when we started this, you mentioned all the books behind me. I’m a pretty literary kind of person these days. And I think that that got me back into it.

And although I was joking about my undergrad years, I knew when I was really bad, I finished off reasonably strongly with a couple of papers. I had to be quite rigorous about it. And I think that connected my underground with the CCC program with what we were going to do in the future. I think that did make a difference. People poo-poo sometimes the academic process. But it’s actually quite useful.

[0:21:39] RT: And rigorous and demanding.

[0:21:40] MY: Rigorous and demanding. It forces you. You keep notes. You keep references. You connect things. You connect the dots. You say this affects that. You move around. You kind of move on and you say, “The paper I wrote halfway through CCC, the faculty didn’t really know what to do with for different reasons.” I ended up changing the subject and I did something completely different. I think that process was really useful.

[0:22:02] RT: And, Martin, how did it inform your work coming out of it?

[0:22:07] MT: Well, the very immediate thing, I was doing some consulting as I came out of the program. And, well, just the fact of having understood a little bit about complexity theory. Complex, adaptive systems helps me enormously. Because just seeing these different informal structures within an organization, some of which were fighting against each other and some which were would have been supportive if only they’d been linked. It helped me in a way that I just couldn’t possibly have seen before I did the program.

And what I was learning through the program, we started off with scenarios. We then did some psychodynamic stuff about – well, all these were about change managing. Ways of changing. Ways of seeing things differently. And they all fitted into the sort of patchwork quilt that I was building up in my mind and helped me deal with life, with work and with tumultuous change in different contexts.

And I couldn’t have kept doing what I was doing without seeing that new way. And a bit like Mick, once you get into the disciplines of research work and noting, analyzing, re-examining, standing back and looking at the bigger picture, that becomes very addictive. Because it’s such fun.

And it’s not the sort of learning that you get at school or from certainly an accounting intuition. It’s all about training. And do this. Do that. And this is about thinking. And it’s such freedom to be able to do that work. And I just loved it. And I still love it. And what I’m doing, I’m not getting any money for at the moment. Because I’m contributing to, hopefully, the development of accounting for sustainability. And no one wants to listen to what I’ve got to say. And it’s certainly not paying me to say it. But I’m saying it anyway. And in a few years’ time, people will look back and say, “You know what? That wasn’t far off the mark.”

[0:24:51] RT: So much for not having anything to say. Mick?

[0:24:54] MY: Yeah. Exactly.

[0:24:57] RT: All right. All right. The story doesn’t end there. You finish the program. You get your degree. You get your distinctions, et cetera. But you have already alluded in the very first module that you were up to something beyond what you had signed on for in terms of the group of people and the learning. And you followed on that. And that’s sort of where I come into the conversation a couple years later.

But tell people what you created during the time you were together as a group. Knowing that when the thing ended, the convening structure that the two schools had put together that ensured you’d be together for six sessions was going to go away. I don’t even think I know all the details of this. I’m going to learn some stuff here, I’m pretty sure. But you had this idea. And tell people what you did and what you created. Mick, why don’t you go first?

[0:25:44] MY: Yeah. It was a group of I think about five of us that were really into this idea of creating a community practice in that first module. And we decided we were going to put together a charter. We were going to put together a code of ethics. We started with a code of ethics actually. And we were going to do this by putting something out after the first module, which was towards the end of 2003, and let people poke around in that. And then when we got back to the second module, have a proper discussion about it.

That first module, we called it the Oxford Network, which was a bit boring. But we kind of had a name for it actually even coming out of the first module, the Oxford Network. And we did draft a code of ethics and we did draft some other stuff. And we shared it with people by email before the second module.

And come the second module, we decided we were going to start to have a meeting before the module. We literally try to get people to Paris or Oxford the day before the module started to just do what eventually became the change leaders business. That’s kind of how it started.

There was a group of, like I said, about five of us that were really into it. Maybe six. And we gradually got other people interested in this idea. By the end of the program, pretty much everybody. I think almost everybody. Maybe less one. But everybody signed up for this idea.

And we tried to make it as – well, it wasn’t totally democratic. But it was certainly a community. We tried to get people’s ideas about how we wanted to make this work. What we wanted to do with the group. And we realized that just doing a community practice with no purpose was pointless. That never works. You’ve only got to read the literature to know that’s true.

The purpose was very much about helping each other’s business. And it was also about helping each other’s learning and personal development, as well as providing some kind of socially interesting forum. I mean, that’s kind of what we said. We came up with the name the change leaders about halfway through that first year. I think it was in the fourth module. That would be about July of 2004 we’d come up with the change leaders idea.

We did do a vote of different people coming out with different ideas and wasn’t totally satisfactory. Some of us came up with a better name. And that’s actually what happened, the change leaders. And the rest, as I say, is history. We had a process using the facilities. We did involve the people that were running the CCC program, Elizabeth and Denny. They were co-opted into our little group especially towards the end of the program.

And then after that – I’m sorry I’m talking a. But you did ask about the process. I’m trying to explain it.

[0:28:30] RT: That’s fine. Go ahead.

[0:28:31] MY: And then what we did was we came along to pitch the second module with what we’ve been doing. And –

[0:28:38] RT: Second cohort.

[0:28:40] MY: Sorry. Second cohort. That’s correct. I’m sorry. And, frankly, there was debate. There was debate amongst us as whether this was just the first cohort’s thing or whether it was a multicohort thing. Because nobody was really sure how long this program would last. Including the faculties, frankly. There was debate about that. But we wanted to go for it.

I think the second cohort was a little bit reticent, frankly. But we all kind of got over that. And then we started this program of meeting twice a year in Oxford or Paris. Not at the same time as the CCC modules. And that got going, well, pretty much straight away. I think we had our first meeting about 6 months after the end of the first cohort. And then after that, it was regularly on a six-month drumbeat. And Martin was unanimously elected as the chairman. He can speak to that himself. I’m not sure he wanted to do it. But he definitely got voted to do it. And off we went.

[0:29:41] RT: Martin, do tell. What would you add to Mick’s version of the birth of the change leaders?

[0:29:46] MT: He’s right. There was a hardcore of five or six of us. Other people called in, checked out, whatever. But we kept going. The Oxford Network idea or name was frowned upon by the people from HEC, which I understand that. It’s a joint effort clearly with two equal parent organizations. It seemed to us that it was not unreasonable to find something that was not focusing on one rather than the other.

And I agree with everything that Mick was saying there. I would add only that the two things that cost us money were setting up a website, which we did, to publish what we were doing and what we stood for. And it was embryonic. But it did cost money to do it. And we did pay for that.

And we had a corporate entity company structure, which cost us some money to set up and required reporting. It was an English law-registered company. And that requires directors, and annual reports, and auditing and one thing and the other which cost some money as well.

Sorry to bring the financials in there. But that was always a consideration. In the end, as Mick said, the last module in which we met, we had to consider whether to open it up to future cohorts or not. And we said, “Well, it’s going to be just a bunch of buddies like this,” which is nice. And there was some good arguments for that. But we felt that it would be a better organization if we opened the doors to all future completers. We didn’t say graduates, but completers, of the CCC program. And that’s what we did. And it became – well, you know, better than we do, Rick, how successful it became. Because it’s gone on for 20 years now. And it’s still going strong. And it’s still meeting twice a year.

And I remember, from the start, we needed about 20 people to turn up to make it viable. And we never had a meeting in which we failed to get a quorum of 20 participants, which when you think that the first year we only had 25 people that were on it.

[0:32:29] RT: Pretty good. It’s pretty good.

[0:32:32] MT: Not a bad accomplishment, I think.

[0:32:33] MY: Yeah. And in fact, some of those – just to add to that. Some of those people dropped out in the first year anyway. We ended up with less people completing. The other two points that worth mentioning maybe is that we were very strong on the brand. We wanted to make sure we had a good brand identity and we had the logo, which is still basically used today by the change leaders.

And the other thing that was really quite important to us, but it was independent of the academic institutions. Although it was sort of, if you like, spawned by Oxford University and HEC, this wasn’t a university alumni group. This was an independent community of practice run independently with its own agenda, its own offices and so on and so forth. And that was really quite important to the founders of the change leaders.

[0:33:22] RT: I’m going to jump what probably seems like an inappropriate distance in time to almost today. But I want to do that because, Martin, you referenced this. But I want to pay some respects here, I think, I know. That you’re right. It’s 20 years on. There was just a conference in Oxford a month and a half ago. Mid-September as usual. I was not there, but you both were there. And I thought it was just karma of a certain kind to see the photos coming across of, Mick, you doing a module for the change leaders with this mongrel collection of attendees now. because you got 20 cohorts to draw from. And so, every time that gathers, it’s a new group. And here, 20 years on, you’re back in the group in the front of the room in the group. You’ve been in the room a lot doing work.

And so, what was that like? I’m really sorry as hell that I missed this gathering with you guys. But life was the way it was. But what was it like to be in that position 20 years on seeing what you had birthed and where it was today?

[0:34:31] MY: Well, I think there’s a bit of a backstory first to that, and that it’s fair to say that neither Martin and I have been to all of the meetings in recent years. I think it’s fair to say for different reasons. Happy to talk about that. But life moves on. We kind of popped in and popped out. Even though one of the founding members, Jacob Maine, had been always at the meetings.

We’ve all got friends inside this group that’s now stretched for 20 years. And one of the people that was organizing this particular program at Oxford knew that I was doing a lot of photography stuff. Knew that I was doing a lot of teaching and was interested in some of the ethics stuff. And said, “Well, why didn’t you just do something?”

And as it happens, it is the 20th anniversary year of TCL. 2023. And Martin, myself, Bessel, Jacob, Billy, Nick, we decided to get together anyway to have a bit of a – well, a social conversation about years of it. It was good actually to come to Oxford and hang out like students again basically. Though we wouldn’t recommend where we were staying. But we’ll not really talk about that too much.

Yeah. What was it like? It was actually quite cool. I mean, I didn’t know what to expect. I have a bit of a sense these days that the TCL of 2023 is perhaps slightly more serious about its mission than we were. I mean, Martin might comment on that. I don’t know. I think they’ve got an interest. They’re bringing a lot of outside speakers. We were always quite keen on having people inside the modules do the speaking, frankly. But there’s been a lot of outsiders come to it. And there’s been a bit more faculty involvement maybe. I don’t know.

The idea of one of the TCL people doing some sharing of what they’ve experienced was kind of back to basics as far as I was concerned. And that was exactly how it always was meant to be. And I decided to make people work. I took them out of their comfort zone.

I basically set up the idea that photography can make change happen or at least can record change and can be useful to change. But it had ethical considerations. And I sent them out on the streets of Oxford to go take a photograph of something that was important to them. And then send me that one photograph back in the joys of the internet, which I would then share with a group, which we did.

It was a bit of a teaching exercise if you like. But it was also connected to change. But it was very much about the group actually doing something. And it was meant to be fun, which again goes back to the beginning of TCL. I mean, we can be on this podcast and say all these wonderful words and define what a community practice looks like and talk about [inaudible 0:37:08] and all kinds of other things.

At the end of the day, we wanted to have a bit of fun doing this. And so, it was kind of back to basics. And as you probably realize, I’m pretty used to public speaking. That hardly phases me at all. Yeah, long answer to a short question.

[0:37:24] RT: That’s fine. That’s good. Martin, what was it like to be back? You’ve had different times where you’ve been in the front of the room. I don’t know if you were there this time around, but you’ve been a fairly consistent contributor to the community from the inception. What was it like to be back with your mates?

[0:37:40] MT: It was good to be back with mates. It was good to meet some new people and some of those people that are a generation younger than we are were stimulating. It was great fun to be there. And fun was actually part of what we were looking for going back to the very first times that we met. And we didn’t have to organize stuff. It just happened. And we were quite happy for it to happen and encouraged it.

[0:38:13] RT: Good.

[0:38:13] MT: I think that thread has run through the years with us. But Mick made the point that, from the very beginning, we knew that we were going to learn at least as much from each other as we would from the academic input. And don’t wish to be disparaging about academic input because it was clearly a big part what gave us the buzz when we were there.

But the link between the real world and academia is where there’s a gap and it’s always an interesting area to work in. And without real academic conceptual frameworks and without feet on the ground in the reality of what’s going on, those two channels can go off in opposite directions or at least not in parallel directions. And they really need to be linked together. And I think that’s a very fertile area of work, which we all really enjoyed.

[0:39:25] RT: Yeah. Okay. All right. I have a couple different questions. Take you out of that and into present day here. The question, Mick, for your side, I’m going to alter it a little bit. But my father was a writer. Newspaper writer for years. And he used to tell me, “You write the book and then the book rewrites you.”

Martin, you are a writer. And, Mick, you’re a photographer. I’m going to say, for your benefit, you take the pictures and then the pictures rewrite you. I’m going to give you a moment here to reflect on your endeavors to put your ideas out into the world in the two forms that you do and just sort of play with how are you different. Because you spent this time putting thoughts on paper or images out into the world. How has that changed you?

[0:40:17] MY: Yeah. I think it changed me quite a lot actually. I’ve never been asked that question before. Thank you. That’s an interesting question. As I mentioned right at the beginning, I did a master’s in photography not too long ago. And I decided to do a project on Cambodia, which is dear to the heart of my wife and myself. Because we did some work there with schools with the government, save the children and so on and so forth. And the Khmer Rouge actually. We have a long history with that country and the people.

And to do my master’s degree, I decided I would use the kind of the rigor I got from my first master’s degree and do a project on the people that had helped manage this program, which I never really properly covered. I’d taken lots of photographs of the schools and the people, but I’d never really taken photographs to tell the story of the people that helped re-engineer the Cambodian education system, which is in fact what we ended up doing. We ended up re-engineering the whole country’s education system for primary schools.

And I started trying to take their portraits thinking that was the way to tell their story. And discovered that was absolutely not the way to tell their story. I ended up doing a combination of text about what happened to them during the genocide in the late 70s with the current situation with mass graves in Cambodia. Because everybody knows about the killing fields. But actually, there are 20,000 killing fields in Cambodia.

That’s a long preamble. I’m sorry. But it’s important to answer your question. How did it change me? It actually changed the way that I think about telling stories. Because I was trying to tell a story that was more than 50 years old through taking photographs today. And that’s a pretty hard ask. And I had to reply some of the academic rigor obviously to get a degree, but also to do the research.

I mean, how do you show genocide? How do you do that? And how do you tell the story of people that suffered and lost 30, 40, 50 of their family members? How do you actually take a photograph of that that made some kind of ethical sense? I think it did change me. I think it changed the way I look at the ethics of photography. And I think it changed the way I talk about it when I teach it quite a lot. Yeah, I hadn’t really thought about that before. But that’s a great question, Rick. Thank you.

[0:42:32] RT: You’re welcome. Martin?

[0:42:35] MT: Well, your father’s dictum, the book Changing Me, was absolutely spot on. I mean, just having the discipline to keep thinking about change processes and to do the work to publish the book, which I’ve worked on with my co-author for six or seven years before it actually got published was what dictated the rest of my working life.

And I don’t suppose I’ve got much more working life now anyway. But we wrote together a book called The MultiCapital Scorecard, which enables environmental, social and economic impacts be brought together. And it requires a normative framework. So it just saying what’s happened is not good enough. Because we’re trying to produce – we have produced something which can help organizations to themselves become sustainable. And none is at the moment.

And I remember a lecture of mine when I was first start studying accounting. And he said, “Now I’ve written this book,” he said, “and if any of you ever think of writing a book,” he said, “just don’t.” He said, “The work that I thought I’d done and therefore could just roll into a book was not 10% of the work that I’ve had to do to complete and publish the book.” And he was spot on.

Except that it was not the answer to not do it. Because if you’ve got it within you and you feel that it’s a communication challenge, then it’s worth it. And I feel it’s worth it. I mean, I’m not earning anything from that thing at the moment. But it shaped – it’s given me a framework, which the accounting profession is still looking for. And we published it. And I’ve given it to the accounting profession before it was published. And I’ve got nothing back from them of significance. And they’re still looking for it. And they still haven’t found it. And, yet, it was published in 2016.

That’s what has kept me going is the inquiries from people that recognize that there’s something in it that need some help in interpreting it for their circumstances or helping them to resource it or to frame it in a way that is useful to them. And all those things are possible. And I’m still available and active to do things on that front when people have got the interest to work on it.

[0:45:40] RT: Okay. Cool. And I have a copy of your book right over here on the shelf. And I’ve read it. I don’t have your signed autograph on it though. I’m going to schlep it with me the next time I come across and I’m going to get you to sign it.

All right. We’re coming down to the end here, guys. This is a podcast that has an orientation towards leading. And as we were discussing before we started recording that part of my orientation is there are younger people on the journey behind us and they could learn some things from this conversation. My question to you is what brief counsel would you have for somebody who’s trying to use themself to lead in their life or in their world? Lessons you’ve learned? Something you thought, “Man, I wish I’d known that?” What advice do you have? Martin?

[0:46:24] MT: Well, first of all, the ambition to be a leader was not something that was part of me or has driven me in any way. Getting together with people that have got similar ideas – we’ve all got gaps in our knowledge of everything. But a group of people that are trying to do something with purpose together is what drove us and what drives me still. If there’s a leadership role, well, just someone will step up and take the leadership role. It’s not an ambition to show that you’re more of a leader than the others.

And, probably, when the change leaders group asked me to chair the first, I could do it. Because I didn’t have a day job at the time and others did. I could spend the time on it that it required. But it was not because I wanted to be the leader or whatever. Leadership, it was once defined as a leader is the member of the group that is able to provide what the collective needs to be successful in what they’re aiming to do. And what that need is changes in every context. There’s not a formula for it. But the people that do the humblest things can be the leaders if that’s what the group needs.

[0:47:55] RT: Right.

[0:47:55] MT: It needs more of those sorts of leaders than it does charismatic, dominant, forceful people that want to prove their own worth.

[0:48:08] RT: Worth. Mick, what say you?

[0:48:11] MY: Well, I mentioned right at the beginning, I never really thought of myself as a leader. And I really still don’t frankly. I used to have a question I asked people when I was interviewing them. The question was this, “What do you stand for?” And some people were absolutely terrified by that question. And other people were not. It wasn’t really a trick question. There was no right answer. It was just a sense of who you are as a person. What is it you are as a person? What are you trying to get done?

And I think my project for CCC was to define a leadership model as I use, which I won’t go into detail now with. But one of the important points on that is the value system that’s got to be congruent between the so-called leader and the rest of the group. And I think bringing out what you stand for and then figuring out the values, sometimes people might call that the culture that you’re involved with, you’re trying to create or trying to change, I think are fundamental. Because there’s a lot of stuff out there and read the book or get a consultant to tell you how to get from A to B. But unless you got yourself pretty much squared away, and unless you know what you stand for and what your value system is, you basically don’t have a hope in hell of getting anybody to follow you.

And then the second point I would say is that – or maybe it’s the third point, sorry, is that there is a unique role for a leader. I’ve tried really hard over the years to wipe the leader out of the model. And it’s like why can’t this group just do it? Why does it need a leader to do it? Why is that important?

And the only reason I can come to is to why that’s important. The leader is like an engine. It’s like a source of energy for the group. And I completely take Martin’s point about charisma and strength. Though I would say that that can help provide the energy. And I think that the leaders got to be able to propel the group not just in the good times and the rah-rah stuff, but when shit’s happening and it’s really bad. And then the leader needs to step up and push, and make it happen and energize people basically. That’s what I know.

[0:50:13] RT: Thank you. All right. We’re kind of at the end of this. We are at the end of this. Not kind at the end of this. We are at the end of this. But, personally, I just want to thank both of you for the wisdom, the insight, the blind luck that’s all in there that you had at the very outset to construct a community that needed to build itself. It keeps needing to build itself every year, every time there’s a new cohort. But none of that probably lives on to 20 years if it hadn’t been for the hard work that you did. On behalf of all those people who are part of the change leaders, I say thank you, guys. And thank you for coming to the swamp. It’s been cool.

[0:50:50] MT: Thanks, Rick.

[0:50:51] MY: Thank you very much. Thanks, Rick.

[OUTRO]

[0:50:55] ANNOUNCER: Thank you for listening to 10,000 Swamp Leaders with Rick Torseth. Please take this moment and hit subscribe to follow more leadership swamp conversations.

[END]